‘REALTIME: Making Digital China’, some highlights on the book content

For the last year I coordinated a book looking at how China can inform our relationship with technology. It was published in January by EPFL Press under the title REALTIME: MAKING DIGITAL CHINA.

The first launch event of the book happened in Shenzhen on January 11th as the covid-19 pandemic was silently starting. Two weeks later, the city of Wuhan - where one of the book contributors lives - went into quarantine. I had to stay in isolation for two weeks after exiting China and witnessed the sad expansion of SrasCov2 worldwide.

Our team originally had plans for release events across Europe, the US and even in Wuhan. All were cancelled one by one as the virus presence expanded across the globe. To this day, most of the writers are quarantined in different places on Earth and the travel situation is likely to remain problematic in the following months. Most activities are now happening in-house or online, so we collectively decided to hold an online release of the book.

The event will happen Thursday March 26, 10-11pm CET (4-5pm CDT), as part of the Virtual Thursday Gathering hosted by the Venture Cafe in Saint Louis, MO (USA).

The online event will include talks by authors Dino Ge Zhang, Dennis de Bel, Maria Roszkowska, Nicolas Maigret, Gabriele de Seta, and Clément Renaud.

The lectures will be kept short to provide some highlights on the book content, then we will bring the discussion on digital technologies in the face of covid-19 pandemic, with experiences from China and across the globe with each present contributor.

What you can expect to find during the discussions :

-

First-hand accounts and observations from the field in China

-

Multiple angles from science, art, design and technology

-

Makers/Makerspaces in China

-

Shanzhai Culture

-

The city of Shenzhen

-

Rural E-commerce Villages and new distribution and infrastructure networks

-

Online folklore and practices - such as damnu

-

China’s role in the past/present/future of technology

Below are short excerpts of each chapter of the book for Makery’s readers to get a sense of the perspectives compiled into this publication. More content is available on our project webpage: http://realtimechina.net

“Technology, before being from any specific nation, is deeply human.” – Clément Renaud

March 25th, 2020

INTRODUCTION

Clément Renaud, Florence Graezer Bideau & Marc Laperrouza

[REALTIME] intends to provide an account from the digital and urban worlds of China. For decades, scholars, think tanks and agencies, both local and global, have been observing and predicting the rise of China’s technological power. Research about technology in China has mostly attempted to understand and describe its local specificities, often in order to make recommendations and adjust for competitive advantages. This book asks a different question: how can China inform our relationship with technology?

This volume is composed of two sides—graphical on the left, textual on the right —so as to offer the reader an experience that is both analytical and sensory. It contains perspectives from researchers and practitioners across various fields including geography, anthropology, economics, design, architecture and art.

CONCLUSION

Clément Renaud, Florence Graezer Bideau & Marc Laperrouza

More than reaching definitive statements about China, REALTIME constitutes a modest attempt at capturing the pace, scale and depth of the country’s complex reality. The book gathers different views and perspectives with the hope of casting a different light on the changes occurring not only within China, but across the world.

The extension of the practices and phenomena observed here, and their correlation to changes in natural and sociopolitical ecosystems, is yet to be explored further. How are these real-time transformations reshaping the human condition? What sort of new physical and conceptual spaces are required to describe and analyze them? And furthermore, how can such spaces exist beyond actual scientific and national boundaries?

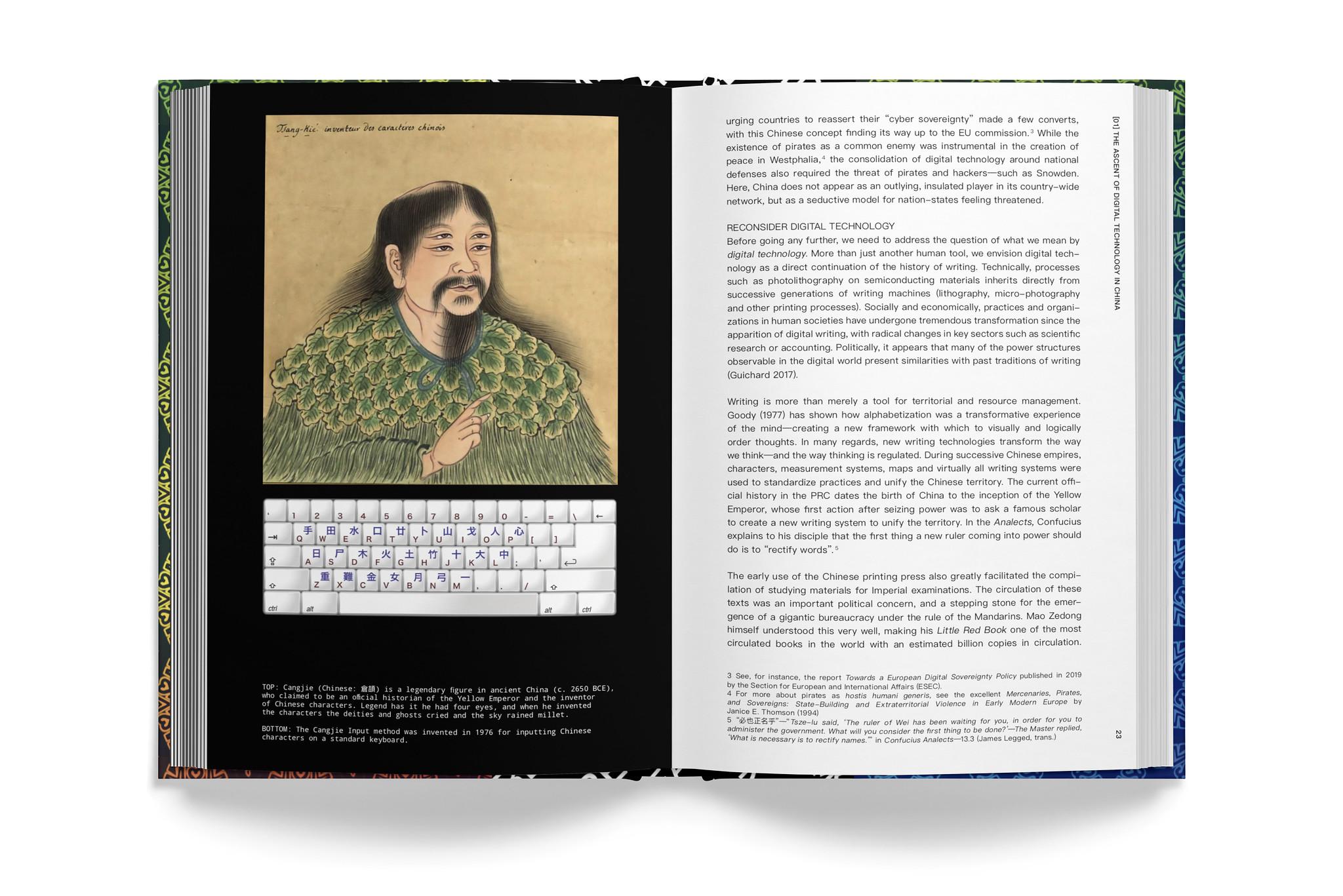

CHAPTER 1 - THE ASCENT OF DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY IN CHINA

Clément Renaud

Digital technology should not simply be considered as a communication tool (the “media”), nor as an infrastructure, but more as a new writing and control capacity.

Supporting versatile life experiences, Chinese Internet companies provide infrastructure, capital and occasionally high-profile role models—like Jack Ma from Alibaba or Pony Ma from Tencent. Their services have become not only a daily habit but an important constituent of social stability. As builders of the key infrastructures of a new Chinese society, they operate not only closer to the government but as an integral part of the country’s administration—even though they may have been privately structured.

The integration of these diversified private companies into the core competencies of public institutions somehow contradicts the image of digital technology in China as a centralized government. Companies, as providers of advanced writing and logging systems, have mandates—either solicited or imposed—to perform tasks for public service.

Beyond the quest for efficiency via automation stands the larger project of building a technological system able to transform not only society but each individual. Social apps and websites exist in this process as major instruments to redefine not only practical abilities but also spaces of representations where new possibilities appear. Like the novels of 19th-century Europe, the new digital writing system aims at making humans more prolific and exemplary by spreading moral, behavioral and financial injunctions. While the in-app credit score is a prominent example in China, it echoes the case of millions of drivers, free- lancers, shop owners and workers worldwide whose work increasingly depends on social platform rankings.

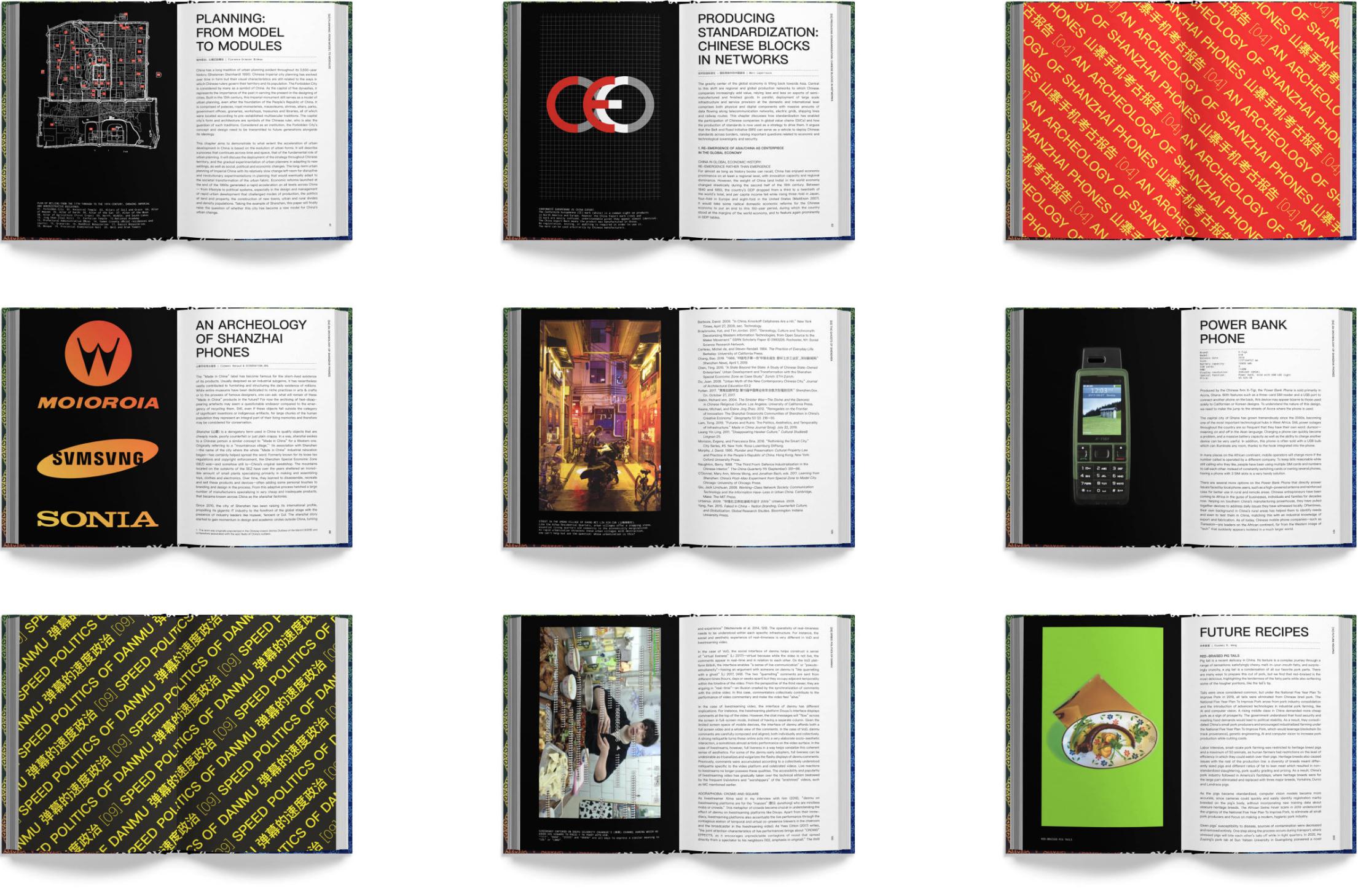

{width=”6.5in”

height=”4.333333333333333in”}

{width=”6.5in”

height=”4.333333333333333in”}

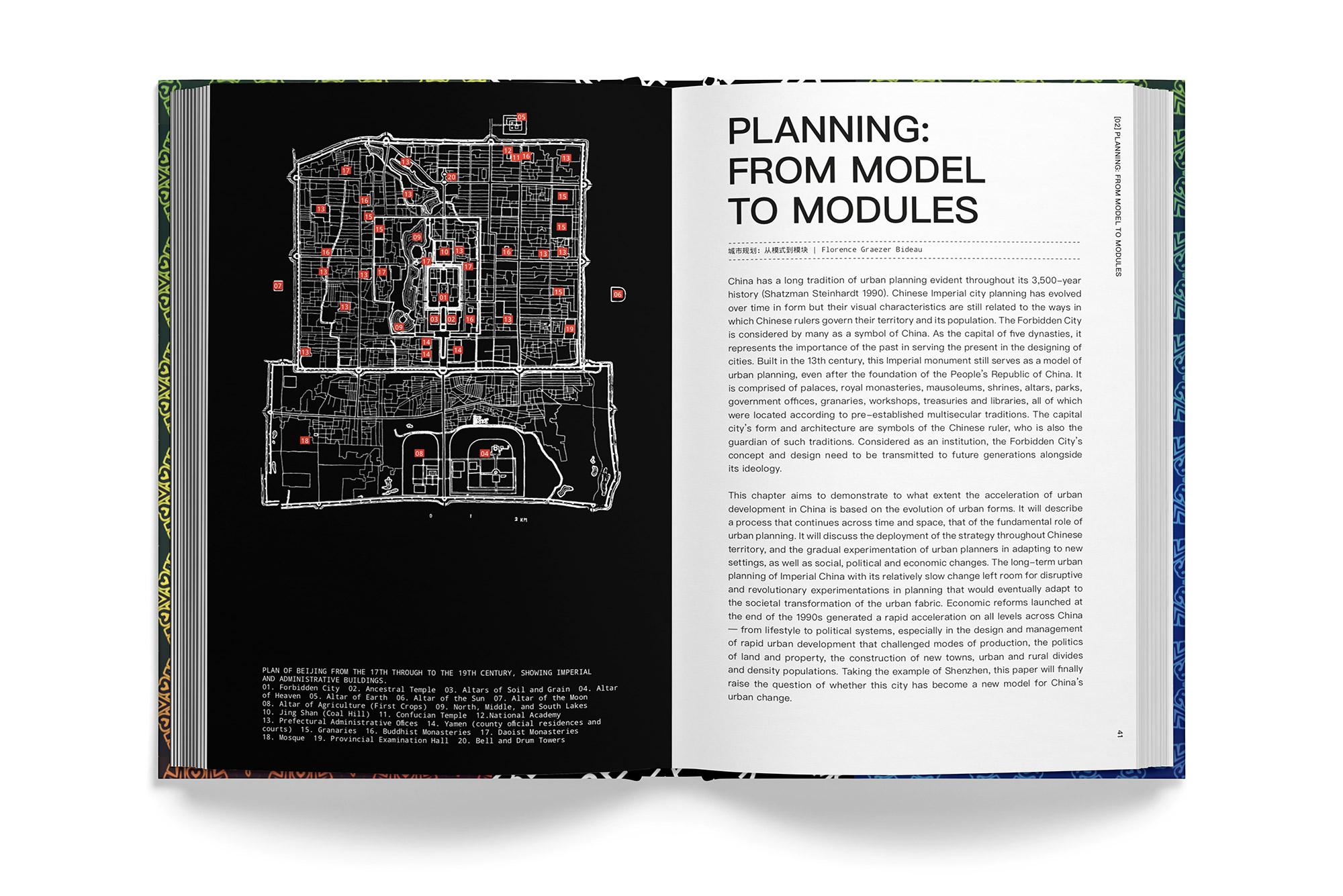

CHAPTER 2 - PLANNING: FROM MODEL TO MODULES

Florence Graezer Bideau

Shenzhen was one of the first experimental sites in China’s economic reforms. As a pilot project, the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone was initiated to com- bine technology, modern governance and foreign experience, and was located in a corridor between Hong-Kong and mainland China. Shenzhen is therefore a relevant example of how capitalist urban development practices were adapted to a specific context where land management was highly controlled by central government (Ng and Tang 2004).

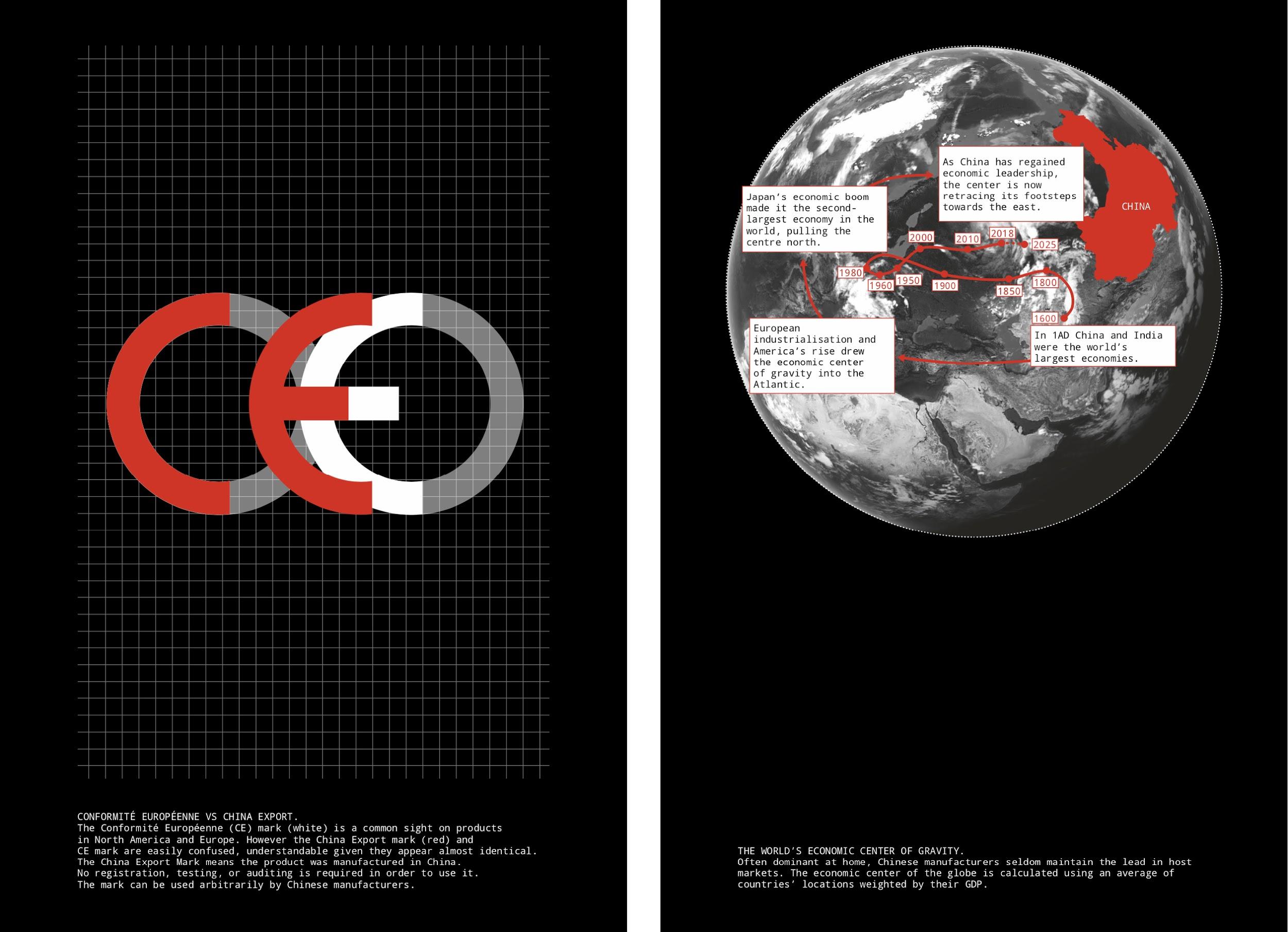

**CHAPTER 3 - PRODUCING STANDARDIZATION: CHINESE BLOCKS IN NETWORKS **

Marc Laperrouza

The fragmentation of production and the ensuing acceleration of trade has indeed been made possible by the stan- dardization of containers initiated in the United States at the end of the 1950s (Levinson 2006). The standardization was actually an attempt to regain competitiveness for US ports by simplifying logistics, reducing overall transport time and, in the end, the total cost.

Fast-forward 50 years and one could observe a similar pattern of standardization in the field of telecommunication manufacturing. Companies like MediaTek, a Taiwanese chipset manufacturer in search of competitive advantage, transformed some parts of the handset manufacturing business by offering turnkey solutions.

The roadblocks thrown onto the deployment of 5G give an indication of the seriousness with which Western governments and companies treat Huawei’s new position in the telecommunication industry.

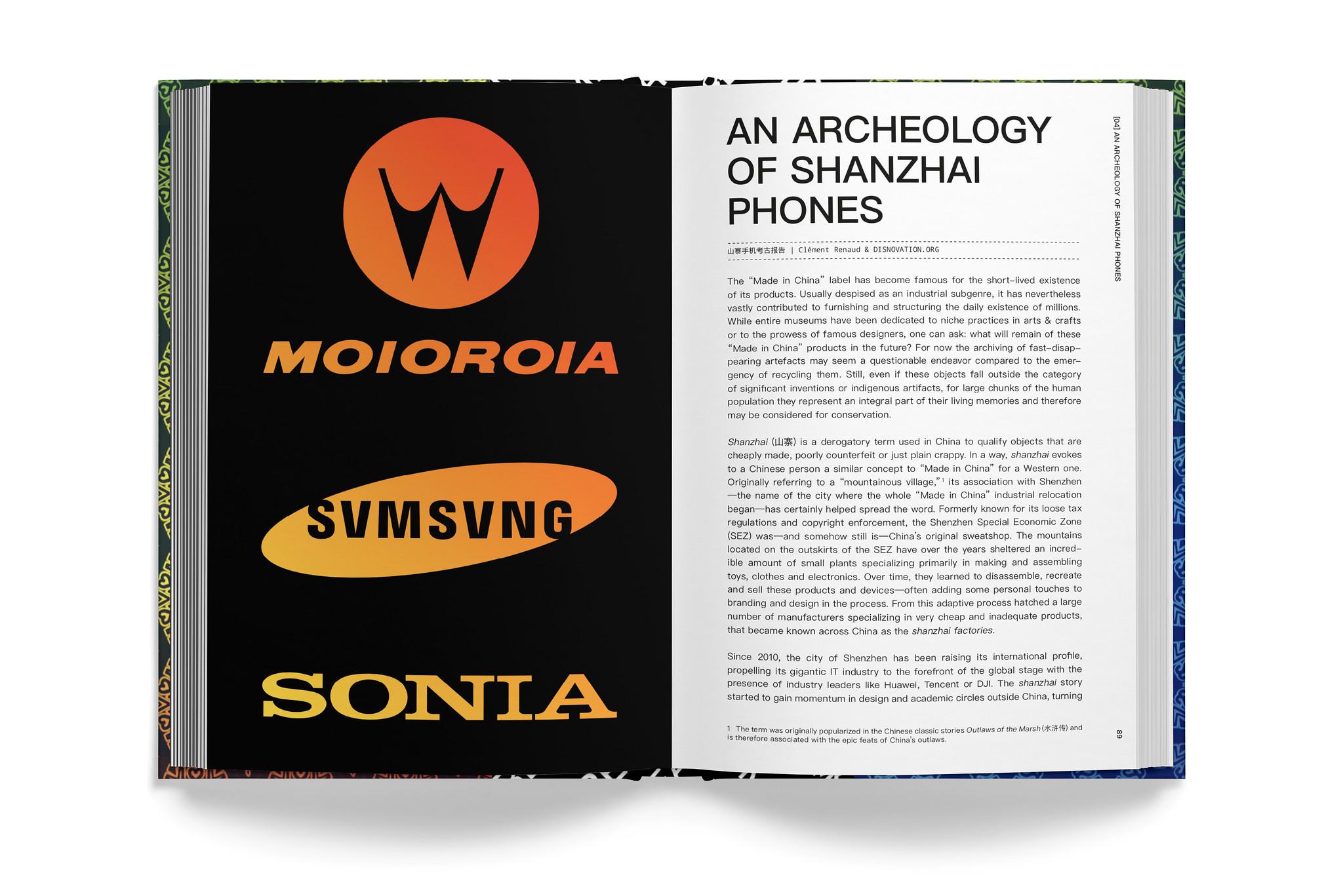

CHAPTER 4 - SHANZHAI ARCHEOLOGY

Clément Renaud & DISNOVATION.ORG

The most interesting thing about a phone shaped like a strawberry or one with its own gas lighter is that, by simply existing, it screams how standardized and boring the Western imaginaries of technology have become.

For archaeologists, fragments of a biface help evoke past realities by providing information about the gestures that created such an object. The shape of a biface evolved from a human hand that dictated a de facto form factor (Ingold, 2013). Despite this de facto standardization force, its original functions (to cut, to drill, to flatten, etc) have since dispersed, evolving into multitudes of shapes and colors. For the phone, the convergence of all designs towards a black-square- with-rounded-corners can be attributed as much to the shape of the hand and eye than to the organization of production lines and shipping of cardboard boxes.

The act of bringing and displaying Chinese artifacts to Europe bears a striking resemblance with the orientalist cabinet of the 19th century. This parallel is amusing in several different respects. The discourse around coun- terfeiting has been present in the background of most discussions about the Chinese electronic industry, with shanzhai located right at its lower end. During our research, we discovered the interesting story of the Jesuit priest François Xavier d’Entrecolles (殷弘绪 Yin Hongxu) who was born in Lyon in 1664 and died in Beijing in

- Father d’Entrecolles arrived in China as a missionary in 1698, where he was praised for his deep knowledge of the Chinese language and sent to Jingdezhen—the capital of the famous art of Chinese porcelain —to appreciate the highest levels of refinery in the Empire. In a letter dated September 1712, the missionary related to his French correspondents that he had finally managed to witness firsthand how the precious pottery was cast, revealing in detail his host’s secrets that would, a few decades later, give birth to the European porcelain industry. It is somehow ironic that Victorian England and Napoleonic France’s most refined goods originated from such a blatant case of industrial espionage—and counterfeiting on a continental scale. By counterfeiting a Chinese kiosk of counterfeiters, we keep alive this long lineage of piracy and the looting of Chinese knowledge to the benefit of arty European salons. We hope that showing these phones outside China can carry us away from our dominant, one-sided stories about innovation and eventually help us escape our normative imaginaries of technology.

CHAPTER 5 - GHOSTS OF SHENZHEN

Dennis de Bel

Just around the corner on Aihua Road, there are several malls. One specializes in recycling cell phones. The other is the largest second-hand phone market in Shenzhen. Here, at night, the residue of these formal marketplaces finds its way to the street and into the backpacks of the many eager customers. To navigate under the veil of darkness requires at least a torch, but to inspect the quality of the piles of phones and logic boards available from the street vendors requires more specific tooling. Amidst the hot and noisy crowds, numerous customers carry devices closely resembling something wielded by ghost hunters, taking readings of electromagnetic fields.

This tool, or “portable charging test power supply” (随身充电测试电源 suishen chongdian ceshi dianyuan) in the words of a trader interviewed in 2018, is a bricolage of consumer electronics held together by hot-melt glue or electrical tape. It is made of a USB power bank, an adaptor for the plethora of USB variants and an analog ampere meter to measure electrical currents drawn from the bank. Sometimes it’s outfitted with an extra USB LED torch for specific use at night, or alligator clips for more general testing purposes.

CHAPTER 6 - LEARNING ABOUT MAKERS IN CHINA

Monique Bolli, Anaïs Bloch, Emanuele Protti, Clément Renaud

In 2015, a large public investment policy called Mass Innovation, Mass Entrepreneurship (众创 zhongchuang) transformed the landscape of making in China (Wen 2017). Benefitting from subsidies, new spaces appeared (and sometimes disappeared) in cities all over China. Small organizations and spaces that existed prior to public intervention often faced unplanned and even diffi- cult situations due to the rise of public interest and attention. Spaces opened and closed, people joined and left, organizations changed or disappeared. City governments in Shenzhen or Shanghai supported the emergence of Chinese public figures and companies as representatives of the global maker movement.

One of the unique points of this experiment was the ability to lead fieldwork as a group. Multidisciplinarity existed not as a theoretical approach but as an opportunity to combine skills and approaches to maximize focus during the short timespan of the visits, interviews or events. The reliance on common goals, defined together beforehand, helped each member of the research team to focus on his/her specific craft (maps, inter- views, drawings, etc.) and to benefit from the common discussions and the material produced afterwards. Another key form of complementarity was the difference in familiarity with the actual field itself—Chinese cities. Expertise and more naive takes were useful in identifying blind spots and traversing different levels of discussion and reflection.

CHAPTER 7 - CHINA.AI

Gabriele de Seta

The track’s music video opens with a flyover shot of the fictional Daode Research Laboratory, where a scientist in a lab coat is activating a female android with an injection of a pink liquid. [...]The singer and the android get married and get on with their awkward love life, which includes playing a game of go, watching movies, singing karaoke, reading books in bed, taking selfies and eventually zooming across a neon-lit Taipei in a sports car. Wang Leehom’s Mandarin lyrics explore the dichotomy between AI and ai (“Love, is just one word / but for thousands of generations, humans still don’t understand it / but A.I. can solve all our problems”)

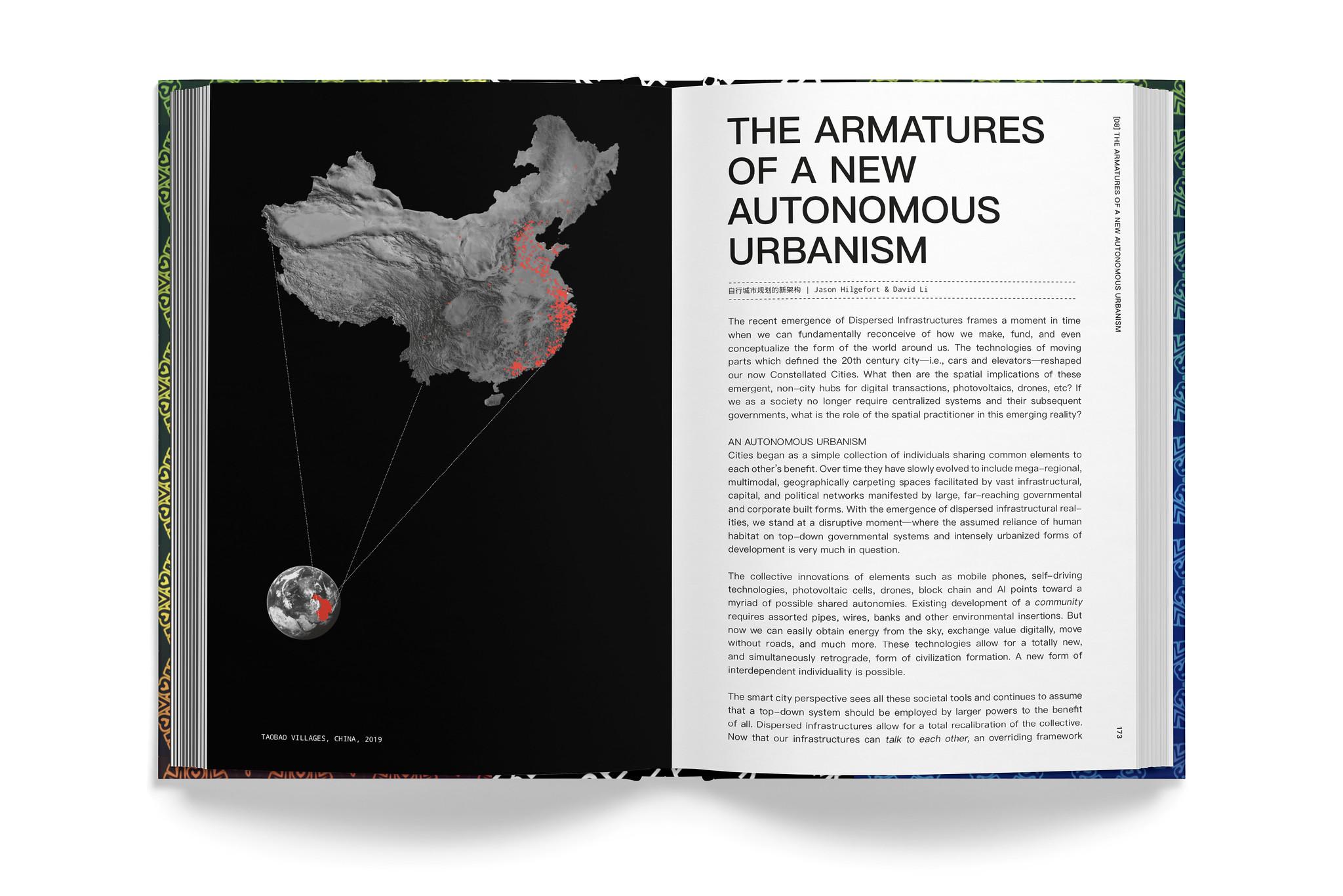

CHAPTER 8 - THE ARMATURES OF A NEW AUTONOMOUS URBANISM

Jason Hilgefort & David Li

Shaji village (沙集镇 shajizhen), a small township of 50,000 in the north Jiangsu Province next to the city of Xuzhou, came into focus for Alibaba Research as it analyzed the e-commerce market in China using big data visualization in 2010. Shaji sparkled on the map as a bright dot of e-commerce activity in middle-of- nowhere rural China. The staff of Alibaba Research were puzzled, and their first reaction was to check the accuracy of the source data. The data was accurate, and the team booked the earliest possible flights to travel to this village.

As they arrived in this rural farming village in north Jiangsu, they met people young and old working in front of old computers in their e-commerce shops. These people processed orders and handled customer service from their humble houses. In the backyard of their farmhouses, people worked in makeshift facto- ries producing flat pack furniture, packaging it to be shipped all over China. In the early evening, the villagers carried these packaged goods made in their backyard factories on DIY rickshaws produced from motorcycles, to the town’s logistic center, where they awaited pick up for distribution across China.

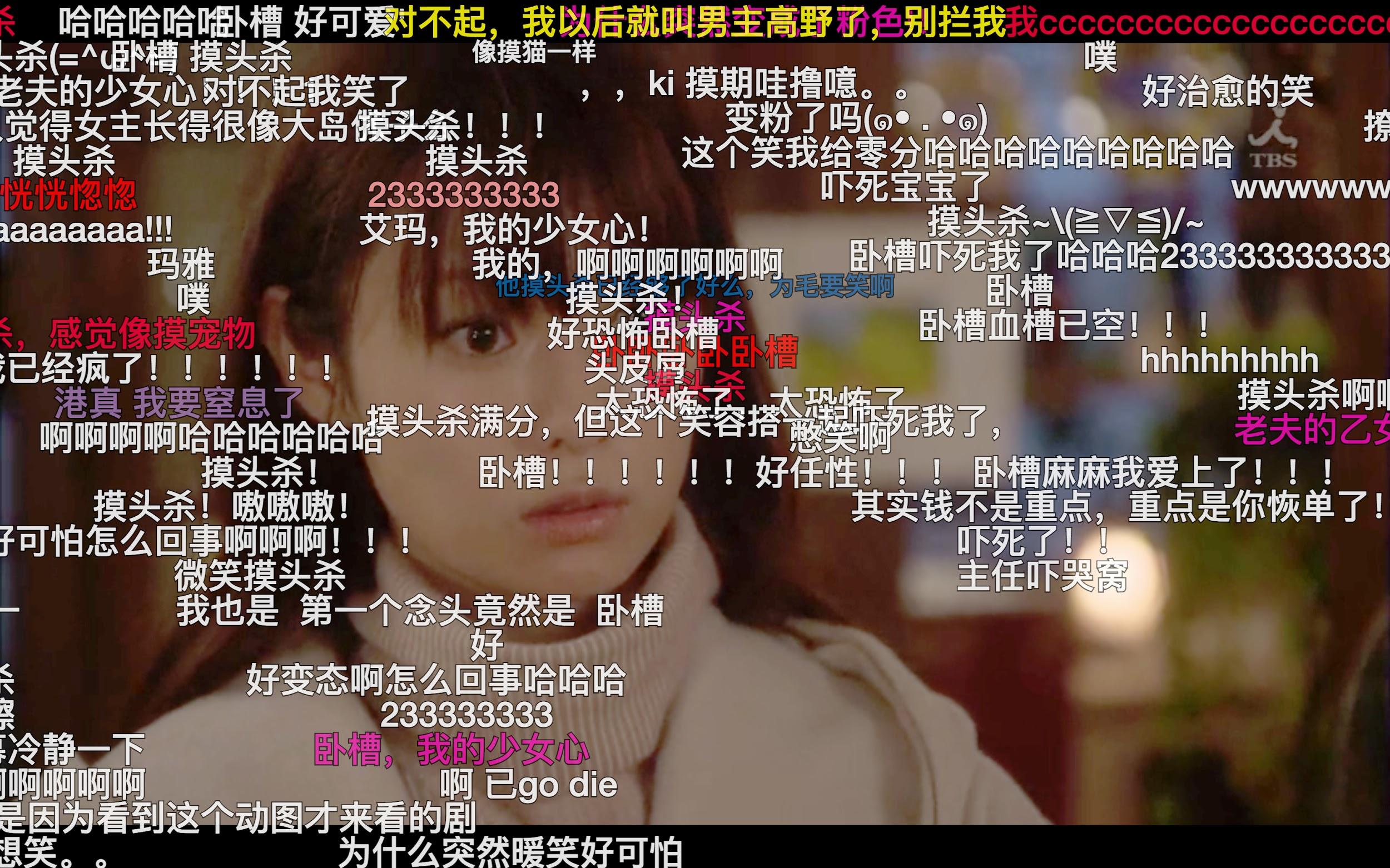

CHAPTER 9 - SPEED POLITICS OF DANMU

Dino Ge Zhang

Appropriating the aesthetic of the rural and the grotesque, MC Shitou fans utilised the comments to simulate the fly-posting of illegal advertisements (often referred to as liupixian or psoriasis) that are omnipresent on the poles, doors and stairs in suburban and rural China. Most of the time, these words were not posted for their literal meaning but as a visual effect via its simulation of the illegal posting of handbills and graffiti—not as static texts but as moving traffic. If traditional comments below the online video (such as YouTube) are the “habitation” of the masses, danmu simulates the flow of traffic—the marching crowd. Both density and speed are crucial measurements of how iconic a video is. There must be a large quantity of comments and they must flow.

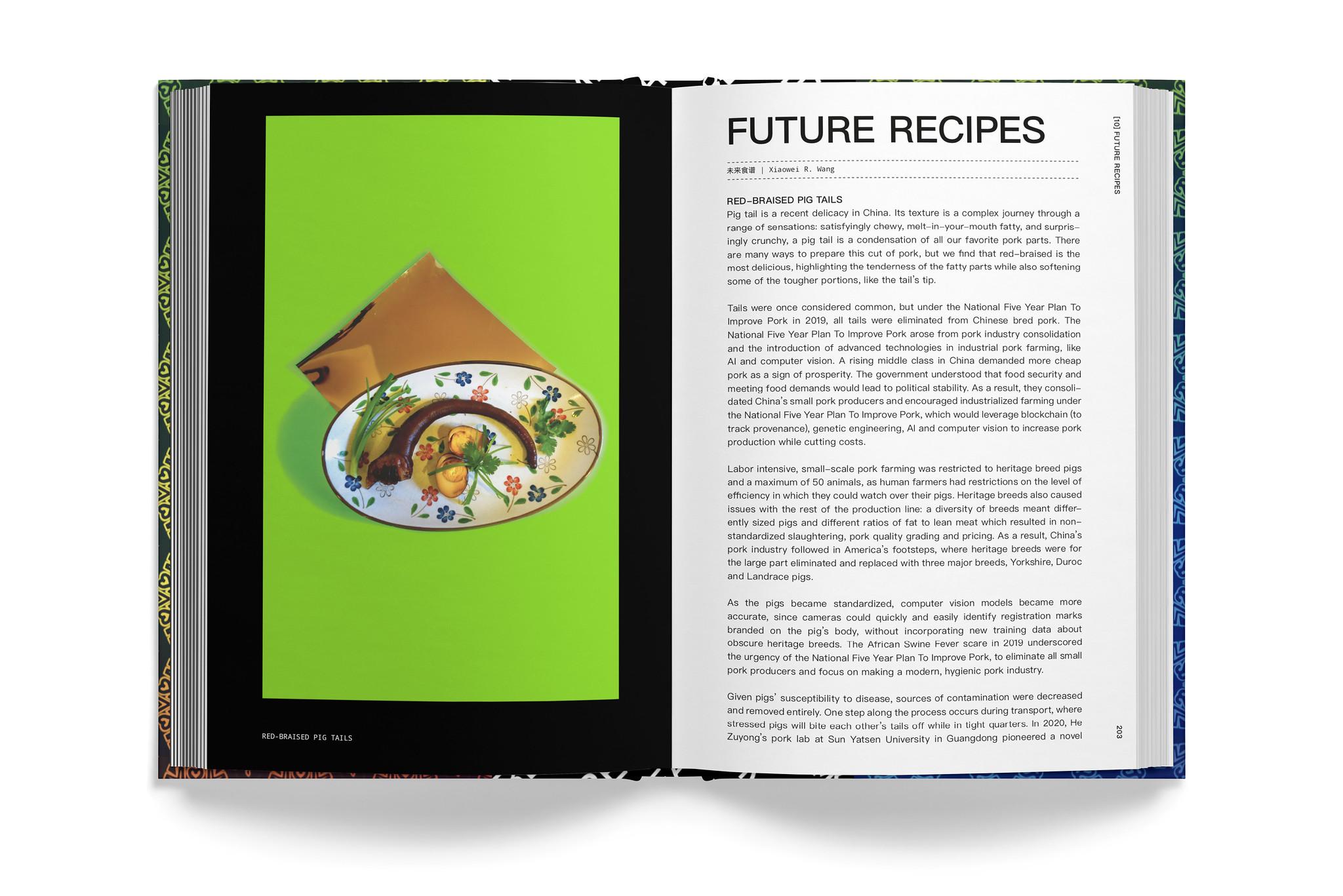

CHAPTER 10 - FUTURE RECIPES

Xiaowei R. Wang

The farmer’s wife profited heavily off her blockchain noodles and received massive amounts of media attention, including a visit from Changpeng Zhao, CEO of Binance who declared she had the tastiest noodles in China. In 2025, after opening a successful blockchain noodle chain, she open sourced her recipe.

This text was originally published in Makery.